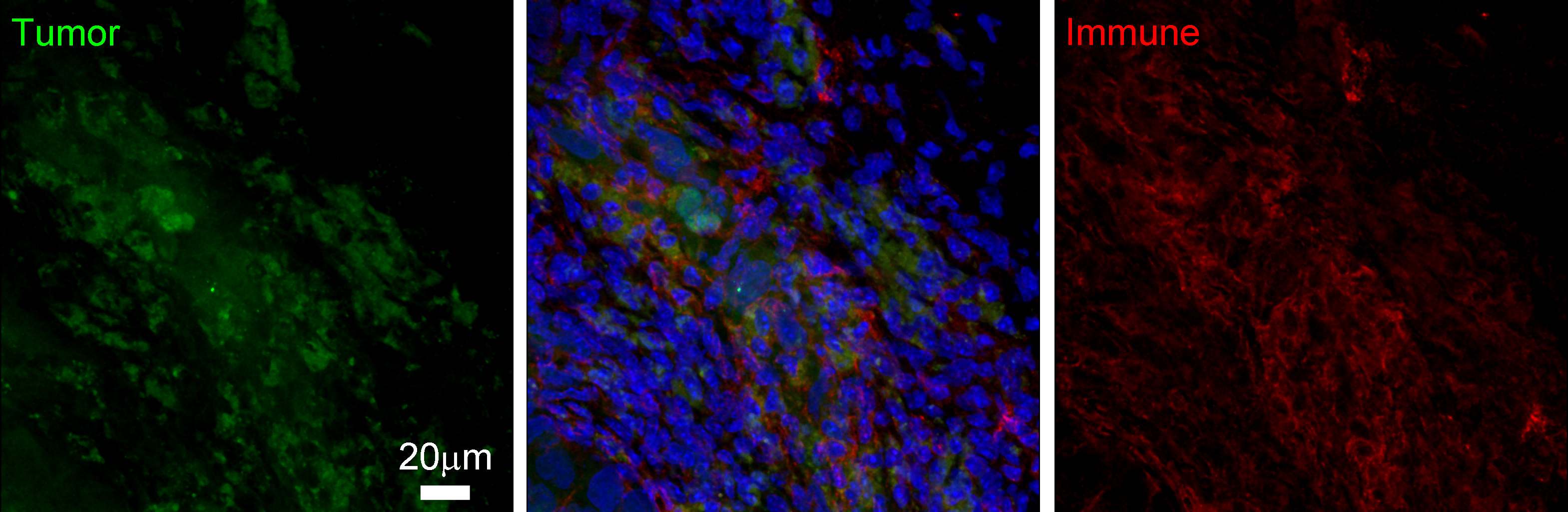

Immune cells can

infiltrate the cancer microenvironment, the consequences of which are not well

understood. The multi-faceted immune presence interacts with cancer cells in

inhibitory and/or stimulatory ways, resulting in complex cancer–immune

interactions. Below we describe our current mathematical and computational

approaches to understand the consequences and implications of these

intercellular interactions.

Tumor-Promoting

Inflammation

The presence of

cancer within a host initiates a systemic immune response towards the

transformed cells. Inflammatory immune cells such as neutrophils, platelets,

macrophages, and natural killer cells, are recruited to the tumor site where

they initiate the wound healing process. Tumors, sometimes viewed as wounds

that never heal, can be promoted by these inflammatory actions. Once the adaptive immune response is

activated by dendritic cells and macrophages, CD8+ T cells, or

cytotoxic T

lymphocytes, infiltrate the tumor and induce apoptosis in the target tumor

cells. Depending on the cytokines and other signals present in the tumor

microenvironment, recruited immune cells will either form a pro-tumor immunity

(typified by cytokines such as TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-10 and cells such as M2

macrophages, Th-2 T helper cells, and myeloid derived suppressor cells) or an

anti-tumor immunity (typified by cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-12 and

cells such as M1 macrophages, Th-1 T helper cells, and cytotoxic lymphocytes).

To investigate the

role of tumor-promoting inflammation, an emerging hallmark of cancer, we have

developed a mathematical model for cancer-immune interactions that can capture

both the pro-angiogenic, tumor-progressing actions of a pro-tumor inflammatory

microenvironment, and the anti-angiogenic, tumor-inhibiting actions of an

anti-tumor inflammatory microenvironment. This model utilizes principles of

generalized logistic growth, which captures some of the inherent variability

underlying tumor growth in an immune competent host that is often neglected in

macroscopic measurements and in mathematical models. From model simulations,

the two types of inflammation (pro-tumor or anti-tumor) resolve into two

fundamentally different classes of outcomes, where inflammation-enhanced tumor

progression must either result in a decreased tumor burden, as in the

anti-tumor case, or in an increased tumor burden, as in the pro-tumor case.

These results suggest that, in some cases, fast tumor growth may be

advantageous, if it leads to a significantly smaller tumor burden. In such

cases, it is possible that treatments should be targeted towards enhancing the

stability of an anti-tumor inflammatory environment instead of towards

immediate tumor regression.

Tumor

Immunoevasion

Despite highly

evolved adaptive immune responses, tumors often manage to escape recognition by

the immune system. This process is known as immunoevasion, and is another

emerging hallmark of cancer.

When hematopoietic

stem cells leave the bone marrow they differentiate into either lymphoid

progenitors or myeloid progenitors. Lymphoid progenitors migrate to the thymus

where they differentiate into T, B, and NKT cells. Myeloid progenitors

differentiate into monocytes, migrate to tissues, and differentiate into

myeloid cells such as dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages. When an immature

DC encounters an antigen, it internalizes the antigen to display fragments on

its membrane. The DC then matures as it migrates to a lymph node. Maturation

involves the loss of ability to engulf pathogens and an increased ability to

communicate with T cells. Within the lymph nodes (collection points where

antigen presenting cells interact with T cells attracted to the node via

chemotaxis), mature DCs activate naïve T cells to develop a specific immune

response. Activated cytotoxic T cells undergo rapid clonal expansion and

migrate throughout the body in search of relevant targets. T cells perform

their cytotoxic function by inducing apoptosis in the target cell through the

secretion of perforin and granzymes or through Fas/Fas-ligand binding.

Within the process

of activating the adaptive immune response described above, two significant

functions may be subverted by tumors: antigen presentation (maturation of DCs)

and T cell functionality.

Antigen

presentation suppression

If antigen

presentation is blocked then naïve T cells are not activated and a specific

immune response is not mounted. A number of cytokines, chemokines and growth

factors, such as HIF-1α, VEGF, nitric oxide, and reactive oxygen species (ROS),

produced within the tumor microenvironment may interfere with the process of DC

maturation. Without DC maturation, there may be an accumulation of

immunosuppressive factors, such as myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), in

the tumor microenvironment resulting in immunoevasion.

In order to

investigate this process from a modeling perspective, we formulated a system of

ordinary differential equations in a predator-prey type system, where the prey

(cancer cells) have a defense mechanism (immunoevasion) against recognition by

the predator (immune system). Our analysis suggests that this mechanism can

have significant effects on overall tumor-immune dynamics, ultimately allowing

for either tumor suppression or tumor escape in a manner that depends on the

strength of the immune suppression [Kareva et al, 2010]. Currently, we are

investigating the possible role of glycolysis and the resulting reduction of pH

in a hypoxic tumor microenvironment as another possible mechanism for immune

evasion.

Impaired

T cell functionality and immune resistance

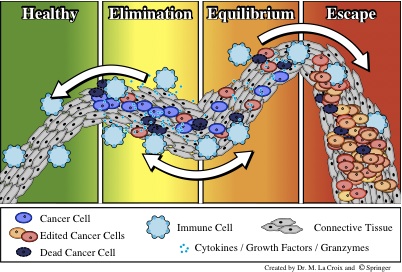

The immune response

poses a second barrier to tumor growth after the angiogenic switch. Immune

surveillance of tissues allows for early detection of transformed cells. If

these transformed cells are not recognized as “self”, they are eliminated by

the immune system. Through repeated exposure of the transformed cells to this

immune selection process, various phenotypes can arise within the cancer cell

population, creating a heterogeneous population of neoplastic cells. These

immunoedited cells may develop the ability to evade the immune response and

grow in an uncontrolled manner.

After prolonged

periods of immune-induced dormancy, T cells can lose effectiveness in their

cytotoxicity. This loss may be due to either T cell tolerization to the cancer

cells or to an increased cancer cell resistance to immune attack. Both of these

mechanisms are intertwined in the process of immunoediting that can lead to

tumor escape from immune control.

To investigate the

heterogeneous population-level dynamics involved in this immune selection

process, we are working on a mathematical model that can capture the essential

cancer-immune interactions that may lead to T cell tolerization and / or the

accumulation of immune-resistance by cancer cells. These two fundamentally

different mechanisms of immune evasion would require specifically targeted

therapies, which could be analyzed theoretically with this mathematical model.

Cancer

Stem Cells and Immune System-Modulated Tumor Progression

The role of the

immune system in tumor progression has been subject to discussion for many

decades. Numerous studies suggest that a low immune response might be

beneficial, if not necessary, for tumor growth, and only a strong immune

response can counter tumor growth and thus inhibit progression.

Without an immune

response, a heterogeneous tumor population comprised of cancer stem cells and

non-stem progenitors grows as conglomerates of self-metastases [Enderling etal., 2009]. This morphological phenomenon results from the interplay of cell

proliferation, cell migration and cell death. With increasing cell death

intra-tumoral spatial inhibitions are loosened, which in turn enable cancer

stem cell cycling and thus, counter-intuitively, tumor progression [Enderlinget al., 2009b]. By overlaying on this model the diffusion of immune reactants

into the tumor from a peripheral source to target cells, we simulate the

process of immune-system-induced cell kill on tumor progression. A low

cytotoxic immune reaction continuously kills cancer cells and, although at a

low rate, thereby causes the liberation of space-constrained cancer stem cells

to drive self-metastatic progression and continued tumor growth. With

increasing immune system strength, however, tumor growth peaks, and then

eventually falls below the intrinsic tumor sizes observed without an immune

response. Focusing only on the cytotoxic function of the immune system, we were

able to observe all immunoediting roles of the immune system: immune promotion

at weak immune responses, immunoinhibition at strong immune responses, and

immunoselection at all levels. Simulations of our model support a hypothesis

previously put forward by Prehn [Prehn, 1972] that comparable tumor sizes can be

observed for weak and strong immune reactions. With this increasing immune

response the number and proportion of cancer stem cells monotonically

increases, implicating an additional unexpected consequence, that of cancer

stem cell selection, to the immune response.

Cancer stem cells

and immune cytotoxicity alone are sufficient to explain the three-step

“immunoediting” concept — the modulation of tumor growth through inhibition,

selection, and promotion. We propose more generally that a stem-cell-expansive

influence may take the form of anything that encourages morphological

fingering. Beyond immune response, this could include cell death, or even

growth within restricted thin channels, as might be expected e.g. during

invasion of host tissue.see more......

Hey to everyone, it’s my first visit of the blog site; this blog includes awesome and actually best info for the visitors.

ReplyDeleteclick for more